http://fixingtheeconomists.wordpress.com/2014/09/22/is-economics-a-science-dogmatic-economics-vs-reflective-economics/

Is Economics a Science? Dogmatic Economics Vs. Reflective Economics

The question asked in the title of this post is actually somewhat of a trick. It is a trick because it all depends upon how you define ‘science’. Often when people say that economics is a science what they are doing is defining ‘science’ in such a way that economics fits the bill. They can do this because there is no real, firm definition of ‘science’ that is widely held among philosophers of science, scientists or, most certainly, among economists (who are the most anti-intellectual of the three groups by far).

If we look at Wikipedia, for example, it gives a definition of science that is Popperian — despite the fact that Popper’s falsifiability criteria have been called into question since the 1960s.

Science (from Latin scientia, meaning “knowledge”) is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

By this criteria economics is probably not a science because it cannot undertake repeatable experiments. Even in a weaker form most marginalist proclamations can be tested and falsified in the sense that they can be shown to not hold given the data we hold yet they remain powerful arguments within the discipline and are taught to students.

Let me then give a different definition of science. I am not saying that this is the correct one but it appears to me to be the one that modern economics as a discipline tried to follow when it was being born in the 19th and 20th century. My definition is as such:science is the search for timeless laws.

Here the obvious reference is Newton and his physics. Now, while we know that Newton’s system was imperfect and was completely overturned in the early 20th century the spirit of what he was doing was, I think, what gave rise to the scientific impulse during the Enlightenment out of which economics was born. When you look at a supply and demand graph you are looking at a representation that is trying to copy Newton by giving us timeless laws. This is also how such constructions are taught to students (any concerns are whisked away using the mysterious ‘ceteris paribus‘ clause).

By this criteria I do not believe that economics is science either. Before undertaking such a discussion I will first lay out my underlying criticism which will be long familiar to readers of this blog: economics deals with historical time which is non-homogenous and thus cannot generate timeless laws. Anything that remotely resembles a functional timeless law in economics is in fact an identity and is true only by its tautological construction.

Let us turn to the precursor to classical economics to give a sense of what I am saying. I am speaking, of course, of mercantilism. In this regard it is worth noting a now somewhat obscure work by the Soviet Marxist economist I.I. Rubin entitled A History of Economic Thought. It has been recently made available online and it is well worth a read.

What is so interesting about the work is that it places the older economic theories in their historical contexts. Rubin discusses each theory with respect to the specific circumstances of the historical situation out of which it emerged. What Rubin tried to show was that mercantilist theory and policy was not a simple ‘mistake’ as the later classical economists tried to portray them. Rather the mercantilist period was a phase of development of the young capitalist states that would go on to conquer the world. He writes:

The basic feature of mercantilist policy is that the state actively uses its powers to help implant and develop a young capitalist trade and industry and, through the use of protectionist measures, diligently defends it from foreign competition. (p26)

When economies had finished with this stage of development and had developed sufficient industrial capacity they were then ready to open up to the world and dominate its markets. It was at this stage that the classical economists arrived on the scene with their doctrines of free trade. This accounts for why the free trade dogma was accepted at different times in different countries. The Americans and the Germans rejected it until the late-19th and early-20th century simply because if they had adhered to it in the early and mid-19th century they would have been dominated by British industry.

Seen in this light it becomes clear that it is fruitless to ask whether an economic doctrine is ‘true’ in some timeless sense. That would be like asking whether, say, feudal law is ‘true’. Feudal law is neither true nor false. Rather it is the formalisation of a code by which a certain type of society organised itself. For that particular type of social organisation it was functional. If we tried to transplant it into a modern capitalist democracy it would probably prove dysfunctional.

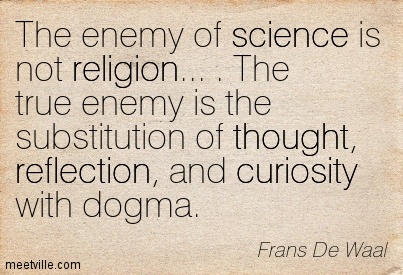

Thus economics, and with it economists, fall into two categories. On the one hand we have what I opt to call ‘dogmatic economics’. Dogmatic economists are basically ideologues. They think that they have access to timeless truths and are scientists in the Newtonian mold. These economists are probably apt to get most things wrong most of the time. They also likely change their basic discourse over and over again. In the face of an ever-changing history they roll with the times, all the while maintaining the pretense that they have access to timeless truths. Basically the interpret and reinterpret their dogmas in light of new facts. The purpose of the dogmas is not illumination, rather it is to lend what they say authority. Dogmatic economists make up the majority of academic economists and also some very high up policy economists in government and economic institutions.

The other category of economics is what I opt to call ‘reflective economics’. Reflective economists understand that what they do is provide interpretations of a given historical constellation. They understand that there are better and worse interpretations — just like a judge can recognise a better or a worse interpretation of a law — but they do not hold to the idea that there are timeless, Newtonian laws in economics. Much of the sort of theory that they promote might be said to be very loose-fitting in that the tools needed for such interpretation tend to be less precise than those exacting constructions put together by the dogmatists. Reflective economists make up the minority of economists in academia. But the vast majority of serious working economists are in practice reflective economists.

What is the relationship between dogmatic and reflective economists in our society? Here there is no firm answer. The dogmatic economists react to the reflective economists in two ways: condescension and deep suspicion/fear. Working economists who do not partake in theoretical debate can be safely condescended to by the dogmatic economists. But the reflective economist who actually tries to engage in theoretical debate will provoke confusion and frustration in the dogmatic economist who is not used to having his or her authority challenged. The main device utilised here is to simply ignore these reflective economists and try to push them out of the debate through social isolation.

The reflective economists also react in two ways to the dogmatic economists. Some build a relationship of what psychotherapists call ‘transference‘ to the dogmatic economists. They assume that the dogmatic economists do in fact have access to timeless truths and that they, the poor working economist, did not make the cut to gain access to these truths. This reinforces the dogmatic economists’ power and social prestige. The other reaction is one of overt hostility. These reflective economists know that the dogmatic economists are Emperors that do not wear any clothes and they make no bones about saying it in public. This makes them quite unpopular with the dogmatic economists who then try to avoid such awkward discussions by isolating the critical reflective economists.